|

Water

covers approximately 70% of the earth's surface, mostly seawater. We depend on the

oceans

and seas mostly for trade and food security. The EU and UN continue to develop

strategies to develop these valuable resources sustainably, presumably

working with all member nations with coastlines. This

'Strategy' is termed 'Blue

Growth.'

STRATEGY

Blue Growth is the long term strategy to support sustainable growth in the marine and maritime sectors as a whole. Seas and oceans are drivers for the European economy and have great potential for innovation and growth. It is the maritime contribution to achieving the goals of the Europe 2020 strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth.

Blue-Action opens matchmaking dialogue between the users of the project modelling data, their analyses and the core scientific groups with the goal of strengthening the competitiveness and growth of businesses which need climate and weather data or analysis for enhancing their existing core business activities that rely on improved forecasting capacity. A focus of Blue-Action is on providing knowledge and security in the blue economy, focussing on marine knowledge, to improve access to information about the sea and maritime spatial planning, to ensure efficient and sustainable management of activities at sea.

In Blue Growth, the programmes support business cooperation, innovation and competitiveness in the marine and maritime sectors. Seas, oceans, coastal areas,

rivers and lakes are drivers of the European economy. They have great potential for innovation, new technology and growth, but the activities along the waters put the resources at increasing risk. The aim of the support to blue growth is contributing to a sustainable

blue

economy.

The aim of the Blue Growth focus area is to address this, and ensure that our oceans,

rivers and lakes are safe, secure, clean and sustainably managed, while remaining an important part of our economies.

THE

BLUE GROWTH FOCUS AREAS

- Blue technologies/processes/solutions developed (new to the market)

-

Blue technologies/processes/solutions applied (new to the enterprise)

Typical activities which are supported Developed and invested in:

- maritime supra-structures

- coastal and maritime tourism

- sea bed mining resources

- blue biotechnology

Development of solutions related to:

- maritime transport

- blue energy

-

blue

peace, sustainable navies

Development of innovative solutions/technologies within:

- fisheries and aquaculture

- marine litter and waste

- water supply, including

desalination.

EUROPEAN

UNION BLUE GROWTH AGENDA

THE (EU) BLUE GROWTH CONCEPT

The concept has started from the notion that maritime economic activities cannot only be captured through a sectoral approach. The maritime (as well as non-maritime) nature of an activity is not necessarily determined by an industrial classification. Blue Growth is the long term strategy to support sustainable growth in the marine and maritime sectors as a whole. Seas and oceans are drivers for the European economy and have great potential for innovation and growth. It is the maritime contribution to achieving the goals of the Europe 2020 strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth.

WHAT DOES THE EU BLUE ECONOMY INCLUDE?

The EU’s Blue Economy encompasses all sectoral and cross-sectoral economic activities related to the oceans, seas and coasts, including those in the EU’s outermost regions and landlocked countries. This includes the closest direct and indirect support activities necessary for the sustainable functioning and development of these economic sectors within the single market. It comprises emerging sectors and economic value based on natural capital and non-market goods and services. The 'blue' economy represents roughly 5.4 million jobs and generates a gross added value of almost €500 billion a year. However, further growth is possible in a number of areas which are highlighted within the strategy.

BLUE ECONOMY AND SMART SPECIALISATION

Smart Specialisation activities support policy-makers, regional and national authorities and other stakeholders involved in research and innovation to bridge blue growth investment platforms and regional innovation initiatives.

Blue economy represents a niche of innovation possibilities for many regions across the EU. One out of five EU regions are

specializing in at least one domain related to the blue economy. Among those domains we can find:

Green

shipping and water transport including highways of the seas; blue

renewable

energy, marine biotechnology.

Smart Specialisation contributes to identify economic activity in the emerging sectors of the Blue economy

Emerging sectors include marine renewable energy, biotechnology, blue biotechnology,

desalinization, deep-seabed mining, and coastal and environmental protection. When addressing emerging sectors of the blue economy, an important concern remains in the scarce level of information and/or absence of statistical data,

standardized indicators and other tools useful to measure economic and innovation impact.

The characteristics and principles of the Smart Specialisation approach help to strengthen economic competitiveness through an inclusive participatory process leading to discover and promote the previously untapped innovation potential and facilitate its market potentials. This approach instigates knowledge exchange among several stakeholders eager to conceive more details and data to support and instruct smart, sustainable, socially effective evidence based regional choices. Accordingly, the Smart Specialisation framework helps to spot blue-growth niches of innovation, including its economic activity.

JOINT COLLABORATION JRC AND DG MARE (ARCHIVE 2020)

In support of the Annual Report on the EU Blue Economy 2019 and 2020, the Smart Specialisation platform analyses policy activity, results and evidences coming from project interventions, collaborative frameworks, industrial advancement and research activity in the so-called "emerging sectors" of the Blue Economy, taking as reference EU regions identifying blue-related priorities of Smart Specialisation.

The analysis integrates elements helping to obtain a deep vision of potential economic impact at regional and member states levels in terms of technological stage, key actors, volume of business, international projection, related strategies, backing funding and indicators.

The geographic scope of this analysis focuses on the EU, paying particular attention to regional, interregional, Member State and macro-regional contexts linked to the Sea basins. The contribution is oriented towards the pre-identification of indicators or set of indicators that will be consistent enough to allow consequent identification, exploration, mapping and analysing of potential economic impact of emerging sectors in the European regions and MSs to create new competitive value chains with innovative products and services.

EXAMPLE

OF EU-REGIONS SMARTLY SPECIALIZED IN BLUE ECONOMY

Place-based innovation is a key element to assure coherence between the territorial dimension and innovation potential. The Smart Specialisation Strategies designed by the EU regions reflect these linkages enhancing the value of local strengths. Regarding the blue economy some regional

specializations target interesting activities of blue economy emerging sector

specializations as follows:

Brittany region (FR), marine biotechnology. Marine Biotechnology focused on macro and

micro-algae, invertebrates, bacteria and viruses constitutes one of the innovation priorities for Brittany. The Smart Specialisation Strategy of this region identifies the potential in industries operating in the domains of food, health, cosmetics,

bio-fuels and green chemistry. The strategy has also identified the close connection between research in this area and the development of new business models of marine living resources, mostly fisheries and fish farms.

Azores region (PT), strengthening research capacity in deep seabed mining. Azores want to become an intercontinental platform of reference for the knowledge of the sea. Accordingly, the Smart Specialisation of this region identifies strategic activities such as:

- Strengthening research in thematic areas with high economic potential such as biotechnology and exploration of mineral resources in

deep-sea.

- Ensure environmental monitoring, aimed at the sustainable exploitation of Atlantic marine resources.

- Strengthening the Azores' external links as an intercontinental platform (notably Europe - America - Africa) in the area of knowledge of the oceans.

Ida-Viru, Estonia, Cross-sectorial dimension of blue economy. This region identifies domains of

specialization in the areas of tourism, health services, wind energy, fish

farming and boat building and repair. These blue-economy based domains are also aligned with the national framework of Smart Specialisation of Estonia in which both new and emerging sectors co-exist as a way to drive economic development. The map shows how these

specializations take place in different territorial entities of Estonia and

neighboring Baltic Sea regions.

Schleswig-Holstein (DE), Participatory process and knowledge flow. The Smart Specialisation process in this German region identified "maritime economy" as one of the five domains with innovation potential. The decision was taken as a result of inclusive dialogue aiming at

mutual-sing knowledge and bringing regional economic perspective. Over the process, territorial actors from public and private sector, academy and civil society were actively engaged. With this decision, the Smart Specialisation Strategy endorses policy interventions and commits funding in the areas of maritime technologies,

specialized ship construction, offshore energy, and maritime biotechnology and production facilities, among others.

Canary Islands (ES), the added value of universities to support innovation niches of the blue economy. The Smart Specialisation strategy of this Spanish archipelago recognises the added-value of universities. A relevant role for supporting the innovation of regional economy is attributed to the local network of Universities and research centres, each covering a

specialization across a wide range of innovation areas. Applied research and technical platforms to test specific solutions are essential in the region to promote innovation in mature sectors (e.g. tourism and shipbuilding) and to position the region within innovative niches with high potentials (e.g. ocean energy) through international strategic partnerships with research centres and industries. A strategic role is also played by the local cluster, acting as a bridge between enterprises and research.

Ireland, policy coherence measures and synergies between national and regional levels of administration. Ireland has promoted a

reorganization of administrative structures at regional level, as a mean to respond more effectively in the innovative sectors identified as priorities of Smart Specialisation. A marine coordination group has been established with senior officials from a range of relevant Departments from the Central Governments and the agency dealing with the policy. Regional Assemblies are functioning as a bridge between national policies and regional needs, so to assure that local priorities and specifications – also the ones regarding blue growth are respected in the implementation of the central government actions. Importantly, a network of brokers has been set up so to engage with local entrepreneurs and other economic actors, to assure their understanding of administrative functioning and to identify potential interesting project ideas to be funded.

Portugal Centro (PT), interregional cooperation and value Nets. The development of value chains associated with the natural endogenous resources in marine environments is a specific domain of

specialization included in the regional strategy of Portugal Centro region. Conservation and sustainable monitoring of these natural resources as well as the development of new products and services constitute innovation niches aiming at reinvigorate the economic development. These priorities are also synergised with a regional innovation hub on endogenous resources which combines expertise from different entities and stakeholders.

Nation-wide, Portugal has mapped the existing networks of knowledge creation and exchange in the country through an assessment of themes covered by local nodes and their integration, including

blue

economy. This approach has allowed for an initial understanding of the current status of knowledge exchange. As a second step, the extent to which such networks interact with the key sectors identified by the

Smart Specialisation strategy can measure advancements and improvements of such exchanges through regional investments. This could be done, for example, by comparing local nodes in the networks and existing companies across the value chains of strategic blue economy sectors. By using the initial mapping as a baseline, the effects of the implementation of the

national strategy can be constantly monitored through the assessment of changes in the networks.

Galicia region (ES), a holistic view of innovation. Valorization of the Sea is a concrete priority for the Galician Smart Specialisation strategy. This priority is addressed from a holistic view of innovation which includes not only high-tech innovation but also services and services innovation.

Valorization of by-products and waste generated by production chains linked to the sea, new service business models, improvement in the commercialisation of associated products and services are also part of the actions covered by the strategy. The following shows the different policy instruments identified by the strategy in order to support the

specialization domains.

CASE STUDIES - THE INTERREGIONAL PARTNERSHIP ON SMART SPECIALISATION IN MARINE RENEWABLE ENERGY

Europe has a strong business and technological fabric operating in the energy and marine industry, alongside with excellent marine resources in terms of recoverable energy. Despite relevant technological advances, the deployment of the Marine Renewable Energy (MRE) sector is not increasing fast enough to meet the EU ambitious goals. Aware of this situation, 15 EU regions

lead by Scotland and the Basque Country joined forces to set-up the Marine

Renewable Energy (MRE) partnership. The MRE partnership is based on the previous work of one of the Vanguard Initiative (VI) pilot actions, “Advanced Manufacturing for Energy Related Applications in Harsh Environments” (ADMA Energy) and benefits from synergies between both initiatives.

The main strategic objective of MRE partnership is to support European companies to improve their competitiveness as suppliers of products, services and solutions with highly demanding requirements in terms of quality, integrity, efficiency and reliability for the marine renewable energy markets (offshore wind, wave and tidal energies), through cross-sectoral and cross-regional collaboration.

To that end, the MRE set up the following operational objectives:

- Facilitate to EU companies the best partnerships in order to address and solve specific challenges at the technological level in the different markets and segments:

- For offshore wind energy, the challenges include increased water depths, more remote and distant site locations, corrosion of towers and foundations and larger size of components, with a resultant increase in logistical challenges for installation, O&M

- For ocean energy (wave and tidal), the current biggest challenge is the survivability of the marine devices.

- Help companies and R&D organisations to establish a better understanding about the critical factors to succeed and develop a long-term vision in close partnership with the relevant stakeholders.

- Reveal visibility of the European industrial potential and help companies to identify their technological needs.

- Help policy makers understand the needs of actors and thus be in a better position to design effective policy responses.

The partnership currently comprises the 16 regions that have identified MRE as one of their key Smart Specialisation priorities based on their present capacities and growth potential regarding the renewable resources available in the region and the technological competences. These regions are: Andalusia (ES); Asturias (ES); Basque Country (ES); Brittany (FR); Cornwall and Isles of Scilly (UK);Dalarna (SE); Emilia-Romagna (IT); Flanders (BE); Lombardy (IT); Navarra (ES); Norte (PT); Ostrobothnia

(FI); Scotland (UK); Skåne (SE); Sogn and Fjordane (NO); Southern Denmark (DK).

The MRE sectors (offshore wind and ocean energies, that include wave and tidal) are experiencing development but unevenly, with differing degrees of technical and economic maturity between the MRE sources. At present, only fixed offshore wind installations can be considered as a true industry sector. The technology of deep offshore wind farms (at water depths greater than 50 m) is still at a pre-commercialization stage and floating substructures are currently at pilot and pre-commercialization stage. The leading developers of tidal and wave devices are on the other hand installing and testing large-scale prototypes in real sea conditions, as well as their first farm of devices.

The complexity involved in the MRE sector leads to higher costs of energy generation than other methods of generating green

electricity.

The higher cost is on the one hand, the result of emerging industry moving from full-scale prototype stage to first arrays. Funding issues, lack of investors and administrative problems can cause the sector to lag. On the other side, the marine environment adds great difficulties, leading to increased investment in deploying cables offshore, building foundations at sea, transportation of materials to more remote areas and installing equipment and turbines at sea.

In 2016 a Technology Roadmap was defined by the Vanguard ADMA Energy Pilot (with a high level of participation of industry through a survey and workshops), to establish a better understanding about the critical factors to success, to develop a long-term vision in close partnership with the relevant stakeholders and to help policy makers understand needs of actors and thus be in a better position to design effective policy responses. The Technology Roadmap stated that the overarching industrial challenge focuses on offering added-value solutions for offshore environments while driving down investment and operating costs in order to maintain competitiveness of the industry.

The key aspects for overcoming the overarching MRE industrial challenge, which focuses on driving down investment and operating costs in order to maintain competitiveness, are shown below:

State of play: Regional agencies and authorities, Cluster organizations, SMEs intermediaries and technology centres from the regions involved have worked together for 4 years with the main objective of improving the competitiveness and international positioning of European SMEs manufacturers of equipment and components.

Partner regions have identified some operational challenges pointed out by their MRE value chain stakeholders, which can be

summarized as follows:

- Few established and systematic relationships exist between companies and organizations.

-

Access to a broad and competitive offer of testing and demonstration infrastructures available in

Europe is complex, due to limited information, lack of alignment between the industrial needs and the offered services and high prices.

- Access to key persons in big customers (facility owners, EPC developers, OEMs) in order to fully understand their core needs and challenges is difficult and limited in time and subjects.

- The process of searching well-matched partners outside their home regions and discussing collaboration agreements is challenging for most companies, and few SMEs are able to invest time and money in this process without assistance.

Information deficiency acts as a barrier to foster any kind of partnering opportunities.

The industry stakeholders agreed on the fact that achieving added-value cost-competitive solutions requires a continuous

technological development and an aggregate thinking of all value chain processes and actors involved. The major technological challenges that companies face in the MRE sectors:

* Corrosion of materials and components in marine environments

* Sensing and remote monitoring in marine renewable energy facilities

* Manufacturing and handling of large-scale components

* Cost reduction of offshore operation and maintenance activities.

The MRE partnership has taken these four technological challenges as the priority fields where common interest initiatives, projects and investments could be developed in collaboration by companies and stakeholders from the different regions. One of the most relevant examples of the pilot projects boosted through the MRE partnership has been NeSSIE, a project funded by DG-MARE that taps into the existing knowledge of anti-corrosion technology/novel materials solutions in the maritime sector supply chain, to develop demonstration projects for offshore renewables in the North Sea . Other example of the joint work of the MRE partnership is the new Pilot Action under the title of “Sensing & Remote Monitoring in Marine Renewable Energy facilities” (S&RM in MRE). This action, financed by DG REGIO, responds to the objective of accelerating digitalization of offshore windfarms and facilitate the acquisition and analysis of the data produced under real operating conditions, in order to generate value for companies at all levels of the value chain.

THE

COMMONWEALTH

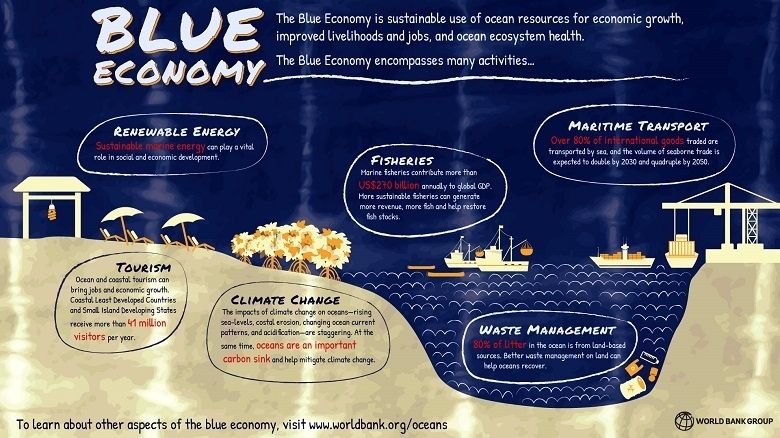

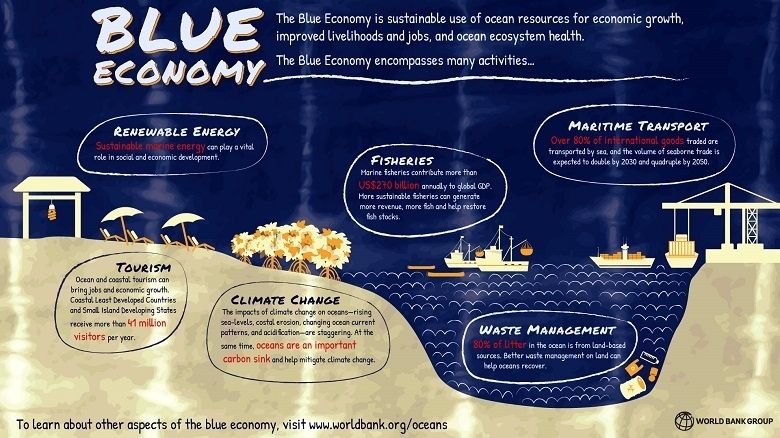

The ‘blue economy’ is an emerging concept that encourages sustainable exploitation, innovation and stewardship of our ocean and its life-giving ‘blue’ resources.

In the old ‘business-as-usual’ model, nations develop their ocean economies through the exploitation of maritime and marine resources – for example, through shipping, commercial fishing, and

oil,

gas, and mineral development. Often, they don’t pay adequate attention to the effect of these activities on the future health or productivity of the same resources and the ocean ecosystems in which they exist. The ‘blue economy’ concept provides a more holistic vision that embraces economic growth – when it is sustainable and does not damage other sectors. Similar to the ‘green economy’, the blue economy brings human well-being, social equity and environmental sustainability into harmony.

The blue economy embraces economic opportunities. But it also protects and develops more intangible ‘blue’ resources such as traditional ways of life, carbon sequestration and coastal resilience in order to help vulnerable states mitigate the devastating effects of poverty and climate change.

The worldwide ocean economy is valued at around $1.5 trillion per year, making it the seventh largest economy in the world. It is set to double by 2030 to $3 trillion. The total value of ocean assets (natural capital) has been estimated at $24 trillion.

Small island states, relative to their land mass, have vast ocean resources at their disposal – presenting a huge opportunity to boost their economic growth and tackle unemployment, food insecurity and poverty. Yet they also have the most to lose from the degradation of marine resources.

Antigua and Barbuda and Kenya are championing an Action Group on developing an integrated approach to the Blue Economy, pushing for the sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth, improved livelihoods and ocean ecosystem health.

This Action Group encourages better stewardship of ‘blue’ resources through actions such as:

- collaboration between Commonwealth countries to exchange successful strategies, information, knowledge and best practices;

- facilitating the deployment of new technologies and innovations to create and drive environmentally-compatible industries;

- developing the economic empowerment and resilience of communities living around oceans, seas, lakes and rivers; and

- building economic instruments to leverage environmental protection, such as blue carbon, blue bonds and coastal resilience insurance.

WIKIPEDIA DEFINITIONS

Blue economy is a term in economics relating to the exploitation, preservation and regeneration of the marine environment. Its scope of interpretation varies among organizations. However, the term is generally used in the scope of international development when describing a sustainable development approach to coastal resources. This can include a wide range of economic sectors, from the more conventional fisheries, aquaculture, maritime transport, coastal, marine and maritime tourism, or other traditional uses, to more emergent activities such as coastal renewable energy, marine ecosystem services (i.e. blue carbon), seabed mining, and

bio-prospecting.

HISTORY

The United Nations introduced the first blue economy during the climate change conference at

Doha, Qatar in

2012. The typical green economy is based on the argument of healthy marine ecosystems for its preservation.

DEFINITIONS

According to the World Bank, the blue economy is the "sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth, improved livelihoods, and jobs while preserving the health of ocean ecosystem."

European Commission defines it as "All economic activities related to oceans, seas and coasts. It covers a wide range of interlinked established and emerging sectors."

The Commonwealth of Nations considers it "an emerging concept which encourages better stewardship of our ocean or 'blue' resources."

Conservation International adds that "blue economy also includes economic benefits that may not be marketed, such as carbon storage, coastal protection, cultural values and biodiversity."

The Center for the Blue Economy says "it is now a widely used term around the world with three related but distinct meanings- the overall contribution of the oceans to economies, the need to address the environmental and ecological sustainability of the oceans, and the ocean economy as a growth opportunity for both developed and developing countries."

A United Nations representative recently defined the Blue Economy as an economy that "comprises a range of economic sectors and related policies that together determine whether the use of ocean resources is sustainable. An important challenge of the blue economy is to understand and better manage the many aspects of oceanic sustainability, ranging from sustainable fisheries to ecosystem health to preventing pollution. Secondly, the blue economy challenges us to realize that the sustainable management of ocean resources will require collaboration across borders and sectors through a variety of partnerships, and on a scale that has not been previously achieved. This is a tall order, particularly for Small Island Developing States (SIDS) and Least Developed Countries (LDCs) who face significant limitations." The UN notes that the Blue Economy will aid in achieving the

UN

Sustainable Development

Goals, of which one goal, 14, is "life below

water".

World Wildlife Fund begins its report Principles for a Sustainable BLUE ECONOMY with two senses given to this term: "For some, blue economy means the use of the sea and its resources for sustainable economic development. For others, it simply refers to any economic activity in the maritime sector, whether sustainable or not."

As the WWF reveals in its purpose of the report, there is still no widely accepted definition of the term blue economy despite increasing high-level adoption of it as a concept and as a goal of policy-making and investment.

According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

(OECD), the blue economy, which includes all industries with a direct or indirect connection to the ocean, such as marine energy, ports, shipping, coastal protection, and seafood production, could outperform global economic growth by 2030.

BLUE TECHNOLOGY

Blue Technology refers to the application of innovative and sustainable practices that aid to a healthier water economy. It's used in nearly every sector to advance or improve existing practices. Examples include

ROVs that can monitor fish farms, robotics that can assist in the effort to regenerate

corals, or vehicles built to remove trash from waterways.

OCEAN ECONOMY

A related term of blue economy is ocean economy and we see some organizations using the two terms interchangeably. However, these two terms represent different concepts. Ocean economy simply deals with the use of ocean resources and is strictly aimed at empowering the economic system of ocean. Blue economy goes beyond viewing the ocean economy solely as a mechanism for economic growth. It focuses on the sustainability of ocean for economic growth. Therefore, blue economy encompasses ecological aspects of the ocean along with economic aspects.

GREEN ECONOMY

The green economy is defined as an economy that aims at reducing environmental risks, and that aims for sustainable development without degrading the environment. It is closely related with ecological economics. Therefore, blue economy is a part of

green

economy. During Rio+20 Summit in June 2012,

Pacific small island developing states stated that, for them, "a green economy was in fact a blue economy".

BLUE GROWTH

A related term is blue growth, which means "support to the growth of the maritime sector in a sustainable way." The term is adopted by the European Union as an integrated maritime policy to achieve the goals of the Europe 2020 strategy.

BLUE JUSTICE

Blue Justice is a critical approach examining how coastal communities and small-scale fisheries are affected by blue economy and "blue growth" initiatives undertaken by institutions and governments globally to promote sustainable ocean development. The blue economy is also rooted in the green economy and the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Blue Justice acknowledges the historical rights of small-scale

fishing communities to marine and inland resources and coastal space; in some cases, communities have used these resources for thousands of years. Thus, as a concept, it seeks to investigate pressures on small-scale fisheries from other ocean uses promoted in blue economy and blue growth agendas, including industrial fisheries, coastal and marine tourism, aquaculture, and energy production, and how they may compromise the rights and the well-being of small-scale fisheries and their communities.

POTENTIAL

On top of the traditional ocean activities such as fisheries, tourism and maritime transport, blue economy entails emerging industries including renewable energy, aquaculture, seabed extractive activities and marine biotechnology and bioprospecting. Blue economy also attempts to embrace ocean ecosystem services that are not captured by the market but provide significant contribution to economic and human activity. They include carbon sequestration, coastal protection, waste disposal, and the existence of

biodiversity.

The 2015 WWF briefing puts the value of key ocean assets over US$24

trillion. Fisheries are now overexploited, but there is still plenty of room for aquaculture and offshore wind power. Aquaculture is the fastest growing food sector with the supply of 58 percent of fish to global markets.

Aquaculture is vital to

food security of the poorest countries especially. Only in the European Union the blue economy employed 3,362,510 people in 2014.

ISSUES

The World Bank specifies three challenges that limit the potential to develop a blue economy.

1. Current economic trends that have been rapidly degrading ocean resources.

2. The lack of investment in human capital for employment and development in innovative blue economy sectors.

3. Inadequate care for marine resources and ecosystem services of the oceans.

WHAT IS BLUE GROWTH? THE SEMANTICS OF "SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT" OF MARINE ENVIRONMENTS

1. Introduction

Governance of marine resource use is increasingly facilitated around a recently introduced term and concept – “blue growth.” This concept is essentially the newest of many recent calls for more holistic management of complex marine social-ecological systems. However, despite use by multiple and diverse stakeholders, the term has no generally agreed upon definition. Instead, it embodies vastly different meanings and approaches, depending on the social contexts in which it is used. The potential for miscommunication is great, as scientists from different fields, as well as other stakeholders, may be using the same term but unknowingly perceiving the concept differently, leading to potential misunderstandings and possibly misguided governance outcomes.

Discussion of the meanings and implications of this increasingly globally important term is badly needed. Although our contributions do not strictly define the term, we hope that those reading this Special Issue will gain a better understanding of the various definitions, as well as a heightened awareness of the constraints of, and possibilities within, the concept. More awareness hopefully will lead to enhanced communication among colleagues and across disciplines and to the convergence towards an operational definition of blue growth necessary to create comprehensive science-based policy that delivers net social and economic benefits as well as benefits the aquatic environment, in particular marine systems.

2. Brief historical development of the Blue growth concept

The roots of the blue growth concept can be traced back to the conceptualization of sustainable development (SD). Sustainable development - or the challenge of a sustainable use of natural resources, while at the same time securing economic and social objectives - has been a focus of the international community since the 1960s. Three large international conferences mark the main milestones in the development of the SD concept: the environmental/resource dimension was defined in Stockholm in 1972 at the first

United Nations (UN) conference on SD; the economic dimension, in Rio 1992 at the second UN conference on SD; and the social dimension in Johannesburg 2002 at the third UN conference on SD. Leading up to the fourth conference on SD, Rio + 20 held in Rio in 2012, a new concept took center stage at the backdrop of the international financial crisis. The concept was “green growth”.

According to the OECD “green growth means fostering economic growth and development while ensuring that natural assets continue to provide the resources and environmental services on which our well-being relies.3” Realizing the traction of this new concept, and the close association of it to growth derived from terrestrial ecosystems, a group of small island nation states (SIDS) emphasized the importance of the blue economy - that is the multi-faceted economic and social importance of the ocean and inland waters - and the importance of “blue growth”.4 At the Rio + 20 conference, the

Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) supported these views and sent a very strong message to the international community that a healthy ocean ecosystem ensured by sustainable

farming and fishing operations was a prerequisite for a blue growth.

Since the Rio + 20 conference, the blue growth concept has been widely used and has become important in aquatic development in many nation states, regionally as well as internationally. The FAO, for example, launched its Blue Growth initiative, the aim of which is to “secure or restore the potential of the oceans, lagoons and inland waters by introducing responsible and sustainable approaches to reconcile economic growth and food security with the conservation of aquatic resources”, and the EU´s blue-growth strategy emphasizes the importance of marine areas for innovation and growth in five sectors in addition to increased emphasis on marine spatial planning and coastal protection.

3. Emerging research

Boonstra et al. Discuss the relevance and usefulness of the term blue growth for the development of capture fisheries, a sector where growth is often accompanied by substantial harm to marine ecosystems. The authors compare intensive and extensive growth to argue that certain development trajectories of capture fisheries might qualify as blue growth. They also highlight aspects of some fisheries that blue growth advocates might want to emphasize if they choose to consider capture fisheries, including:

a) adding value through certification;

b) technology development to more

efficiently utilize resources in fishing operations and to upgrade their fish as commodities; and

c) specialization.

They also posit that the term blue growth is meant to realize economic growth based on the exploitation of marine resources, while at the same time preventing their degradation, overuse, and pollution.

Integrated management of multiple relevant economic sectors is also a central tenet of blue growth, as is a socially optimal use of ocean-based natural resources; but we do not have more than a poor understanding of possible mechanisms for the implementation of integrated policies that would actually achieve this. Klinger et al.

Take steps to fill this gap by reviewing current challenges and opportunities within multi-sector management. They describe the roles played by several key existing sectors (fisheries, transportation, and offshore hydrocarbon) and emerging sectors (aquaculture, tourism, and seabed mining) and discuss the likely synergistic and antagonistic interactions between sectors. To help operationalize blue growth, they review current and emerging methods to characterize and quantify inter-sector interactions, as well as decision-support tools to help managers balance and optimize around interactions.

Burgess et al. Discuss how the complexity of ocean systems, exacerbated by limitations on data and capacity, demands an approach to management that is pragmatic. By this they mean goal- and solution-oriented, realistic, and practical. Burgess proposes five helpful rules of thumb upon which to build such an approach:

1) Define objectives, quantify tradeoffs, and strive for efficiency;

2) Take advantage of the data that you have, which can do more than you may think;

3) Engage stakeholders, but do it right;

4) Measure your impact and learn as you go, and

5) Design institutions, not behaviors.

These rules, if used properly, will go a long way towards encouraging development that is realistic rather than unattainable.

Hilborn and Costello summarize the past and present status, as well as potential catch, abundance and profit for 4713 fish stocks constituting 78% of global fisheries. In particular they focus on three possible scenarios for how the future might look: 1. Business as usual (BAU), in which unmanaged

fisheries move towards a

bio-economic equilibrium, while well-managed fisheries maintain their current management. 2. Maximum sustainable yield (MSY), in which fisheries are managed to maximize yields. 3. Fisheries reform (REF), where competition to fish is eliminated and fisheries are managed to maximize the profits. They found that for most of the fisheries, better management can result in higher profits. In order to increase yields, in some cases it is necessary to rebuild overexploited stocks; in others, we must reduce fishing mortality on stocks that are still abundant but fished at high rates; and, in some cases,

fishing some stocks harder will increase the yield. They also find that Asia provides the greatest opportunity for increasing fish abundance, particularly in cases where increased profits caused by fisheries reform will ultimately lead to a reduced fishing pressure. As the oceans provide food, employment and income for billions of people, reduced fishing pressure and sustainable fisheries are critical for global food security.

Niiranen et al. Discuss how the lack of recognizing cross-scale dynamics can cause uncertainties to the current fisheries projections. They show how cross-scale interactions could play out in two

Arctic marine systems, the Barents Sea and the Central

Arctic Ocean (CAO), by discussing how they are affected by a number of processes beyond environmental change. These changes span a wide range of dimensions, as well as spatial and temporal scales. They conclude that addressing such complexity calls for an increase in holistic scientific understanding, together with adaptive management practices. This is particularly important in the CAO, where there are no robust regional management structures to rely on to curtail potentially sub-optimal developments. Recognizing how cross-scale dynamics can cause uncertainties to fisheries projections, as well as implementing well-functioning adaptive management structures, may play a key role in whether or not we are able to realize the great potential for blue growth in our world's fisheries, PNAS), particularly those in the

Arctic.

Social innovation is the process of developing effective concepts, strategies, solutions, or other ideas that can help solve challenging societal and/or environmental problems via collaborative action by a group of actors. Social innovation can result in changing behavior across institutions, markets or the public sector, and can enhance creativity and responsible action towards a synthesis of social, economic and environmental goals. Is it possible for blue growth to enable social innovation as a strategy for the use and management of marine resources? Soma et al. (this issue) examine this issue using case studies and conclude that this may be possible, but success will be dependent on creating cooperation, inclusiveness and trust between the different actors.

Pauly presents a short history of marine fisheries, highlighting the dramatic expansion of industrial fleets in the 1900s and the intrinsic

un-sustainability of those fisheries. Pauly then argues that while the vast majority of large, commercial fisheries lack the features that would make them sustainable or even capable of sustainability, small-scale fisheries

(including artisanal, subsistence and recreational fisheries) often possess most of these features. Small-scale fisheries could become an

important blue growth sector, assuming total fishing effort is not increased and incentives for industrial fishing are reduced. Unfortunately, small-scale fisheries usually receive little attention from policy makers, as is clearly seen by the lack of small-scale fishery catch data submitted by member countries to the

FAO.

4. Stakeholders’ opinions and outlook

Stakeholders are essentially people with interests or concerns in a process and its outcomes. Generally, these can be employees, directors, owners/ shareholders, consumers, government, or the community from which the business draws its resources. When we refer to stakeholders in reference to blue growth, these extend to such a wide demographic that almost anyone could be considered a stakeholder – the entire population of the planet will be affected, in one way or another, by blue growth (or the lack thereof).

However, we try to focus on stakeholders who have some direct influence as well as immediate interest, and hence who could potentially be part of a solution to achieving blue growth, and thereby contributing to sustainable development. Examples would be owners or managers of fishing companies, fishermen themselves, and government employees. Scientists are also an influential stakeholder group. These stakeholders have the power to make or influence important decisions, and thus are crucial for the actual implementation of blue growth and sustainable development. These are the people we must focus on when we communicate scientific findings that illuminate paths or policy changes that could lead to more sustainable outcomes.

In this issue we also include an article by Brian Clark Howard, who interviewed stakeholders; Jacqueline Alder from the FAO; Maria Damanaki from The Nature Conservancy; and Paul Holthus, the founding president of the World Ocean Council. Gaining the perspective of these and other stakeholders is essential to the development of a common understanding of blue growth that policy-makers, scientists and business people alike can relate to and agree upon. Furthermore, successful blue growth itself is dependent on our ability to communicate across vastly different perspectives. It is not only scientists who hold the key to blue growth; without the cooperation of stakeholders there can be no blue growth no matter what the science and the data tell us. Cooperation and mutual understanding are not easily achieved, but they are essential to our success in achieving the goal of sustainable development.

5. The challenges

Although blue growth has a great deal of potential to secure sustainable use of the oceans, there are some clear challenges. One of the most apparent obstacles is the lack of a common and agreed -upon goal of blue growth. For some, blue growth revolves around maximizing economic growth derived from marine and aquatic resources, but for others it means maximizing inclusive economic growth derived from marine and aquatic resources and at the same time preventing degradation of blue natural capital. This lack of a common understanding may be the reason for the paucity of holistic blue growth strategies and more specific and inclusive goals and milestones that cut across sectors.

Another challenge is inter-disciplinarity – and learning how to “speak the same language”. Not only must scientists work together, across their diverse disciplines; but also scientists must work with policy experts and policy makers, together with other stakeholders who might have even more disparate interpretations of blue growth and other focal terms. Close collaboration with stakeholders is necessary to ensure that research informs and supports viable, integrated, and comprehensive solutions and their implementation. In theory, this seems doable, once the data are in and the conclusions are clear, and communicated to the politicians and policy makers.

Identification of knowledge gaps, which clearly depend on one's viewpoint, is another key challenge. What a scientist thinks is a critical knowledge gap may seem inconsequential to the government body deciding what to fund, and an obvious gap in knowledge for a politician that is critical to a policy decision might also be something that scientists are not focused on. Stakeholders in the industry might have a third idea of what are the critical gaps in knowledge that need to be assessed in order to create sustainable businesses. Again, communication is key here, although power imbalances caused by availability of funding must be closely monitored to avoid biased research, and biases in the knowledge that we gain from research.

Another challenge is how to resolve conflicts of interests, which are often rooted in tradeoffs between different uses of the ocean space, but also often concern who decides what should be open for public debate. For example, in Norway, salmon farming has emerged as an important industry in the national economy, and the sector has pioneered improvements in feeding practices, resource efficiency, and environmental performance per unit of production. However fish farming can have significant environmental and biological impacts in the ocean, which affects other uses of the ocean space. Comprehensive analyis of tradeoffs between different ocean uses requires coordination among and cooperation from very different scientific disciplines and stakeholders. Resolving conflicts between stakeholders is difficult and requires holisitc approach to governance.

Despite these challenges, blue growth has the potential to facilitate collaboration and communication among scientists, industry, and politicians and thereby lead to a coordinated effort to combat the effects of climate change and

anthropization. These challenges require additional research and would benefit from co-development with stakeholders. We hope the work laid out in this Special Issue lays the foundation for this to proceed in the future.

6. Toward a deeper understanding of blue growth

In this Special Issue, we have assembled a broad spectrum of papers that discuss blue growth from a diversity of

disciplines. Interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary research is of prominent importance when discussing the challenges and opportunities for blue growth, especially as one major challenge is to obtain efficient communication between the involved disciplines. Indeed, interdisciplinary dialogues, like this special-issue collection of papers provides,

necessitates that we understand each others’ terminology and concepts. The collection of papers in this Special Issue is meant as a contribution in this connection. In addition to the within-science dialogues, we also need to have a clear and comprehensible dialogue with stakeholders, as reflected in this collection.

REFERENCE

https://www.fao.org/policy-support/policy-themes/blue-growth/en/

https://eea.innovationnorway.com/article/blue-growth

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0308597X17306905

https://s3platform.jrc.ec.europa.eu/blue-growth

https://thecommonwealth.org/bluecharter/sustainable-blue-economy

https://s3platform.jrc.ec.europa.eu/blue-growth#fragment-89005-dzxn

https://thecommonwealth.org/bluecharter/sustainable-blue-economy

https://thecommonwealth.org/bluecharter/sustainable-blue-economy

https://s3platform.jrc.ec.europa.eu/blue-growth#fragment-89005-dzxn

https://thecommonwealth.org/bluecharter/sustainable-blue-economy

https://www.fao.org/policy-support/policy-themes/blue-growth/en/

https://eea.innovationnorway.com/article/blue-growth

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0308597X17306905

https://s3platform.jrc.ec.europa.eu/blue-growth

|